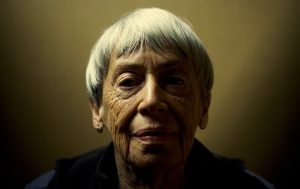

“There are no right answers to wrong questions.” – Ursula K. Le Guin

To truly envision a healthy future, we must first confront the nature of affliction, acknowledging that human systems, being fallible, are prone to imbalance and unintended consequences. Just as the profound insights of medicine often emerge from the careful study of pathology – learning how the body functions in health by observing its breakdowns in disease – so too can we approach the intricate world of economics. This social science is dedicated to understanding the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services; it observes how individuals, businesses, governments, and nations make choices about allocating resources. Yet, for its observations to be truly insightful, they must be unburdened by ideological bias, seeking clarity even in moments of imbalance; this requires a commitment to letting data drive decisions.

Guided by Le Guin’s wisdom, it becomes clear that human fallibility can lead society to ask the wrong questions about the fundamental well-being of its economic systems, inevitably leading to flawed conclusions. It is precisely through a data-driven examination of economic “illnesses” – the crises, inequalities, and unsustainable patterns that plague the present – that one might uncover the deeper truths about how a truly healthy and equitable economy should operate, allowing us to then design effective solutions.

Among these afflictions, consider the subtle yet profound transformation of the household income model. What began, in recent history, as an option for a couple to enhance their prosperity by both venturing into the workforce, has incrementally calcified into a societal expectation, often a perceived obligation. This evolution has, by data-driven analyses, primarily benefited governments, through increased tax revenues, and existing property owners, whose assets have so doing swelled in value. For the typical household, however, the trade-off, revealing a design flaw in our economic evolution, has been significant: a relatively modest increase in material quality of life against a substantial forfeiture of precious discretionary time. This shift helps to explain why, in contemporary society, even highly skilled professionals, such as a single hospital consultant, can struggle profoundly to acquire a tolerable place to live on their own earnings alone, a striking contrast to the past where a working-class family might sustain itself on a single wage.

This paradox deepens when one considers the extraordinary advancements in technology. Today, individuals enjoy unprecedented access to high-quality goods and information – from sophisticated televisions and mobile phones now accessible to almost everyone, to streaming services that offer global content regardless of one’s postcode. These innovations have, in many realms of consumption, delivered a remarkable degree of egalitarianism. Indeed, it has been observed through careful analysis that these widespread benefits of technological democratisation appear to have been disproportionately ‘mopped up in the rivalrous chasing of property assets.’ This systemic redirection of economic gains into inflating property values, rather than broadly enhancing lived experience, stands as a quintessential ‘economic illness’ that we must diagnose with robust data and address through innovative design.

This approach calls for a dispassionate, yet deeply human, observation of economic behaviour, driven by the mantra to ‘let data drive our decisions’. It seeks not to impose pre-conceived notions but to accurately diagnose and learn from the ailments of current systems. Recognition is given that behind every statistic lies a human story, and as Oliver Hart eloquently demonstrated, economic theory, at its best, provides a language to understand and communicate the complex relationships that shape lives, delving into questions of control, power, and the very human need for connection and purpose, all informed by rigorous data.

How do we design an economy that is both efficient and humane? It requires a delicate balance, a blend of practical policies and a poetic sensibility in its design. Just as a well-crafted poem uses language to evoke emotion and understanding, We need to use economic tools to build a society that is both prosperous and meaningful.

Such a pursuit demands not only a nuanced understanding of present afflictions – diagnosed through data – but also the courageous imagination to envision truly transformative design solutions. How, for instance, might we fundamentally disrupt the mechanisms through which basic shelter becomes a conduit for disproportionate wealth, rather than a universal right? History, often a forgotten teacher, offers intriguing precedents. Consider the ‘chattle houses’ of the Caribbean, portable dwellings that allowed residents to physically move their homes to an adjacent plantation if a landowner demanded excessive rent. This ingenious design essentially disentangled the ownership of the dwelling from the ownership of the land itself, granting residents a remarkable degree of leverage and mobility.

Echoes of this concept can be seen in contemporary ‘trailer parks’ in the United States, some of which, far from their humble reputation, foster thriving, desirable communities, even in affluent areas. This prompts a provocative question for modern planners: what if society were to commission leading innovators to design highly desirable, mobile forms of housing? Imagine elegant, modular homes that could be temporarily situated, perhaps even in underutilised spaces like country pub car parks, facilitated by short-term planning permissions. Such a design innovation could fundamentally reshape the property market, re-establishing a form of consumer power and allowing individuals to invest in their home without being permanently tethered to the escalating cost of land ownership. This seemingly radical idea is, in essence, a practical application of the ‘poetic sensibility’ of economics – using ingenuity and design to foster freedom and equity where rigid structures currently constrain.

The pursuits being illuminated are by thinkers who understood the profound, often unquantifiable, aspects of human experience. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great American essayist, believed that a true poet articulates what others feel but cannot express; in a similar vein, We seek to give voice to the unspoken needs and aspirations of society, translating these deep-seated human desires into actionable policies, which are inherently acts of design, that truly serve.

Complementing this, the philosopher John Stuart Mill recognised the vital importance of feeling and imagination in understanding the human condition, arguing that economic decisions are rarely, if ever, purely rational, being deeply influenced by emotions, values, and deepest aspirations. Embracing this holistic view, acknowledging the rich tapestry of human motivation, precisely because understanding these human elements, which contribute to fallibility, necessitates a robust, data-informed and carefully designed approach.

The poet Etheridge Knight reminds that language and metaphor are powerful tools that shape understanding of the world; To harness these very tools to craft a compelling narrative for a better future, one that resonates with people not just intellectually, but on a deep, emotional level, using precise language to articulate data-driven insights and the logic of thoughtful design.

Ultimately, compeling the contemplation of capitalism itself. When a significant portion of wealth accumulation stems not from productive effort or societal contribution, but from the unearned inflation of asset classes, particularly property, it exposes a systemic fallibility where the very principles of fairness and meritocracy become strained. As some have powerfully argued, this phenomenon, identified through careful data analysis, risks discrediting the broader capitalist system in the eyes of the public. It has already fostered resentment when immense prosperity appears disconnected from proportional societal value creation.

We need to dare to ask transformative questions: what if societal prosperity were truly measured by widespread well-being rather than concentrated asset gains? Could a system, perhaps underpinned by a thoughtful land value tax that captures unearned increases in land value for public benefit, alongside a commensurate reduction in income tax – a clear policy design – lead to a future where individuals could maintain a dignified quality of life working, for example, a four-day week? Such a vision requires not just a shift in policy, but a profound re-evaluation of what constitutes true economic progress – a future where prosperity is not merely measured in numbers but in the flourishing of people and the health of the planet itself. It is a vision that demands both pragmatism and poetry, a steadfast commitment to both efficiency and empathy, guiding society towards a more equitable and humane economic landscape through deliberate design.

Where next? Use the links below:

Snippets: Curated collection of short, impactful articles and inspiring ideas.

Forward Futures: Actionable essays delving into contemporary issues.

Grasp the Nettle. Table of Contents: A book in progress charting paths toward a more empowering future, for a global audience.

About: Our mission – From Awareness to Action.

Bibliography

Galbraith, John Kenneth. The Affluent Society. Houghton Mifflin, 1958.

Mazzucato, Mariana. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. Anthem Press, 2013.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press, 2014.

Rodrik, Dani. The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. W. W. Norton & Company, 2011.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper & Brothers, 1942.

Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.